As I mentioned in my last entry, I wanted to try to reduce the number of applications in my toolchain, as well as simplify the process in other ways. My aim was to try to get to the point where I could use only the free tool Audacity. I have found, however, that Audacity has some interface issues that make it very difficult for me to use for the editing stage of the process, and so I have to record & edit the audio in Sound Studio before moving into Audacity for most of the filtering.

To make this a little simpler, I basically see this as a three-step process:

- Record the audio

- Edit out the mistakes

- Filter & enhance the remainder

Let me break it down a little bit more.

First, record the audio. Have your microphone, software, book (or kindle or whatever), studio, hot tea, water, and such all ready to sit down and do the recording. Hang up the signs that say "do not disturb" or whatever you need to do. Then, record your narration. When you are recording, if you make a small mistake (such as skipping over or mumbling a word) make a sharp noise, and start over from the most recent natural pause. I snap my fingers in front of the mic, other people will clap, but whatever it is it should make a distinctive mark in the audio software's waveform representation. This just makes it easier to see later when editing. Then, start over from that most recent natural pause, and continue. Record as long as you are comfortable, and then stop. I always make sure to record a few seconds of the studio in as near to silence as I can before and after. This is called "room tone" and serves several purposes.

Second, once a recording is complete, edit out mistakes. By "complete," of course, I mean once you've finished recording a particular section, chapter, poem, or whatever. You can wait until you've finished recording every section, or you can do each one as you stop recording, it's really up to you. The only caveat there is that for ACX (and for your listeners, even if you don't or can't use ACX for your audiobook publishing), it is important that the entire finished product has a similar sound throughout, so replicating the conditions of recording is vital. Having the finished product meet certain technical requirements (such as ACX's requirements) will help, but if you record several chapters in one location, and then change locations for others, your listeners might notice the difference in quality and background.

In any event, sit down with your editing software and listen to the finished product. Delete any segments where you made mistakes—this is where those snaps or claps come in handy—until you have only the correct narration of your work, with all of the reading mistakes edited out. Then, listen to it again from beginning to end. If you have edited out any mistakes, sometimes it's hard to tell exactly how long a pause should be until you hear it in playback. If you find that a pause is too long, you can always edit it out; conversely, if you've recorded a few seconds of silent room tone you can copy a few dozen milliseconds of it, and use the "paste" function to insert a little extra pause where needed.

Third, once you have a correct narration, with the spacing and pauses and everything else in their proper place, you will want to filter & enhance the sound file. Exactly what, how, and how much will depend on your specific recording environment, software, microphone, and so forth, but here are some tools common to many software packages to consider (all are named using the conventions in Audacity where applicable, although most of them are pretty common names for pretty common sound concepts):

- Noise Reduction

- Compression

- Limiting

- Click Removal

- Ducking

- Equalization

- or Treble/Bass reduction or increase

- Echo or Reverb

Some of these will be a good idea to use on each recording, but the order in which you do them matters, at least in theory. Also, most of these filters/effects/modifications are done on the entire file (except the Ducking, which I explain below).

So, based on my experimentation and output results so far, this is my workflow. Please note that this has not yet been submitted to ACX, and even if it had I can't guarantee your results will be the same, but this setup should at least get you on the right track.

So, based on my experimentation and output results so far, this is my workflow. Please note that this has not yet been submitted to ACX, and even if it had I can't guarantee your results will be the same, but this setup should at least get you on the right track.

I always do a noise reduction first. That should help to prevent any further processing from increasing the sound from the noise, helping to keep the noise floor as low as possible. For ACX, the noise floor can be at most -60 decibels (dB), so removing the noise early makes sense to me. It also makes the next step easier, since the compressor has a much more silent floor to detect.

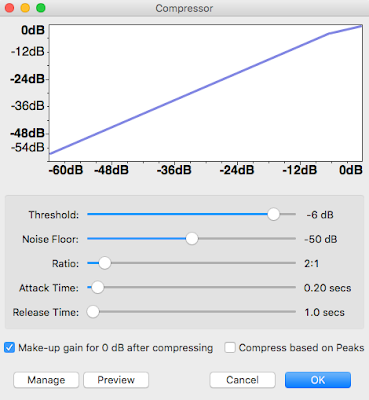

Next, I run a compressor on the file. I use the following settings:

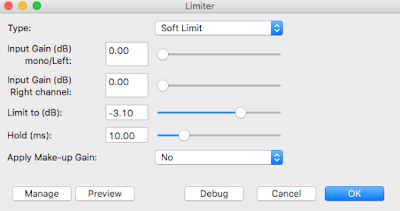

When the compressor finishes, the resulting sound file is quite a bit louder, but the peaks of it (at 0 dB) are too loud for ACX (which requires a max of -3 dB). So my next step is to run a Limiter on the file:

|

| My Limiter settings in Audacity |

Next, I run the Click Removal, which helps to eliminate any stray lip smacking or sharp breath noises I might have made while recording.

At this point, I stop and listen to the entire piece from beginning to end. If I hear any lip-smacks or breathing noise that the Click Removal didn't catch, I will stop and select a few milliseconds before and after the noise, and then duck the audio. Essentially, what that means is that on only the selected audio, I decrease its amplitude so that it is no longer audible on normal listening. (Technically, ducking is when you decrease the sound of a given track below that of other audio present, but the process is the same whether there is other audio present or not, so that's what I'm going with.)

Once I've gotten through the entire file and removed as much of the distracting breathing and lip noise as I can identify, I give it another listen. This time, I'm listening for the balance of treble & bass tone. If it sounds too tinny, I'll use the equalizer to adjust the relative balance of bass, mid tones, and treble sounds. Conversely, if it's too bass-rich, I'll equalize in the other direction. Some software will have specialized equalizer filters for Bass or Treble Enhance (or Reduce), and you can experiment with those to hear how it sounds.

In addition, there's a consideration for reverberation or reverb settings. Initially, I was using a tool in Final Cut called a doubler, which essentially just provides a perfect duplicate of the selected sound only a few milliseconds later (Audacity calls this effect Echo), and has basically the same effect, providing some additional depth to the sound. Reverb essentially takes the sound and uses mathematics to simulate what that sound might be if it were bouncing off of different substances in different sizes of location. The essential difference between echo (or doubler) and reverb is that the echo simply duplicates the sound, with a delay (how long between the original and echoed sound) and a decay (how much of the original sound is reproduced in the repeated signal, each time it is repeated). Any decay below 1 will reduce the sound for each echo, and a very small decay (such as .05, say) will result in the sound quickly dying out. The reverb will simulate the echoed sound being bounced around inside a room of a size you specify (numeric size, not square feet), and has a lot more options to consider. I have experimented with it and have found that a straight echo with a delay of 0.05 second, and a decay of 0.05, gives my vocal recordings more richness without the obviousness of reverberation. However, I encourage you to experiment and find your own settings (and, share them below if you are inspired to do so)!

One thing to keep in mind: if you decide you want to use echo or reverb, I recommend doing it before you apply the limiter, or set your original limiter a bit lower (say, -3.5 or -3.8 dB). The echo or reverb effect may increase the peaks, and if so it may pop you over the ACX submission threshold.

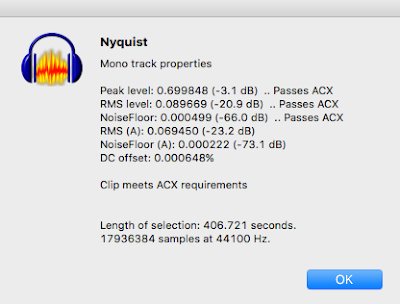

Finally, the last thing I do is run the ACX check on the file. Here is the output from that for my latest recording file:

|

| Output from the ACX Check analysis |

Now, at this point sometimes there are special effects that need to be considered. For example, in one part of With It or in It, I included a paraphrased transmission that was sent over military radio frequencies to our unit on a gunnery range. After recording the audio, I saved the file as an AIFF file and import it into Final Cut (since I couldn't find a plug-in for Audacity that performed this), where I applied the "Car Radio" filter to just that section of the recording. It made that section sound like it was being transmitted over the radio, which was exactly the effect I was looking for. Once done, I exported that file back out as an AIFF and opened it in Audacity to re-check with the ACX Check tool, just to make sure I hadn't messed up the floor or peak levels (mostly; this section was only a few seconds and was unlikely to affect the RMS level significantly).

Once this part has been completed, I recommend sending this file to a trusted friend (or a solid beta reader/listener, if you have one willing to help) for a second set of ears. It especially helps if they are familiar with your book, but this is not strictly necessary. Ask them for their feedback on the overall sound, any distortion, clipping, or distractions that may be present that you missed, and overall flow. Sometimes, you will discover that you thought you cut out a mistake but didn't, or that you accidentally skipped a word, sentence, or paragraph (or, accidentally cut them out).

Finally, when you are ready to submit to ACX (if you are going this route), you'll need to save the finished file as an MP3 file, with a bit rate of at least 192 bps, Constant Bit Rate, and as a mono file if you can (or a stereo if you can't, but do not create a "joint stereo" if your software gives you that option).

So, that's where I am right now with this workflow. During the rest of the week (in addition to other things) I will be working on getting up those videos I discussed before, which hopefully will help elucidate any unclear areas. Let me know what you think by leaving a comment below!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.